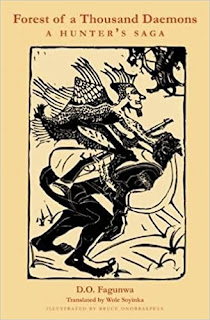

Summerbook #5: Forest of a Thousand Daemons

This is a pretty amazing book and I feel so lucky to have found it. To sum up, this is the first novel written in Yoruba -- one of the first in any African language -- published in Nigeria in 1939. It's a major and influential classic in Nigerian literature which draws on Yoruba folk traditions. Having read the two novels by Amos Tutuola last summer, I can now recognize something of the relationship between the two writers; Tutuola was clearly very influenced by Fagunwa. Wole Soyinka translated Forest of a Thousand Daemons into English in the mid-1960s, and there is a wonderful note about his translation process, in which he comments, "Fagunwa's beings are not only the natural inhabitants of their creator's haunting-ground; in Yoruba, they sound right in relation to their individual natures, and the most frustrating quality of Fagunwa for a translator is the right sound of his language." Obviously, only the smallest portion of Fagunwa's language choices can make it into a translation, but Soyinka really must have done a stellar job at it, because the language is individual and evocative, though I cannot claim to know anything much about it.

The narrator of Forest of a Thousand Daemons is not the story-teller; an old man comes to him and asks him to write down his story. For three days, the man -- Akara-Ogun, 'Compound-of-Spells' -- tells about his experiences, and each day more people come to hear the incredible tales. Akara-Ogun has been a hunter all his life, and a very skilled one, and a few times he ventured into this forest, a land inhabited by all sorts of spirits and beings, which are generically called ghommids. His first adventure involves a huge fight with a strong ghommid, a trip to a village of the dead, and a marriage. Akara-Ogun's second trip is longer; he is captured by a sort of fishy creature who is cruel to him, and only escapes by a trick. He winds up at the court of the king, and becomes a trusted advisor, foiling several assassination attempts. Finally, Akara-Ogun and several comrades go on a quest to a mountain kingdom, and have plenty of adventures along the way.

The forest is a very strange landscape, where circumstances change all the time and all sorts of creatures appear -- such as the one that is like an ostrich with a man's head... It all partakes of a dream-like feeling, and reminded me very much of My Life in the Bush of Ghosts. Though of course it's really the other way around!

...he said to us, "Aha, I observe that you fall silent, and the reason for your silence is this -- the key to this world remains in the keeping of God. Were it in human possession there would be no illness, the poor would not exist, no one would ever know hardship, there would be no servants, everyone would be master in his own house -- and the world would be much worse than it is today." His words amazed us greatly; they were full of wisdom and we changed our tune and began to tell him, "There is truth in this, old man; do carry on with your wise words."

And, it's illustrated with fabulous woodcuts, too.

I enjoyed this novel so much -- it's really, really strange, and it's a great novel, and I certainly did not understand it one bit, and I'm happy that it's currently in print. People interested in African literature should definitely have it on a must-read list. I think it really helped that I had already read some of Tutuola and Soyinka, but also that is not necessary.

Extra thoughts:

Getting to read translated literature at all is a gift, but it's always a limited one, because you can never really get the fullness, the complete feeling, of the original text. Even if I could learn Yoruba, or Hindi, or Russian -- without a truly deep understanding of a language, I couldn't hope to really know the text. (Take this far enough and you'll wind up in Bakhtin territory, and that way lies madness.) I wish I could understand so many languages! It always reminds me of the Grail Knight in the Indiana Jones movie; he could have said, "That is the boundary, and the price, of reading literature in translation."

But Soyinka continues in his translator's note: "The essential Fagunwa, as with all truly valid literature, survives the inhibitions of strange tongues and bashful idioms." So it's always worth reading translated literature; 90% is a lot better than zero.

"Getting to read translated literature at all is a gift, but it's always a limited one, because you can never really get the fullness, the complete feeling, of the original text."

ReplyDeleteI think about this CONSTANTLY. Because I have read a lot of fairy tales, I often think about what I would wish for if like, a genie appeared and offered me wishes and I wanted to make sure my wishes wouldn't hurt anything. So my carefully refined wish is to speak, read, and write with native fluency every language that currently exists on earth, without it damaging my brain's ability to do any of the things it currently does. (You can see I have been refining the wording for many years. :P) I have gotten a lot better about reading translated literature but I still just ITCH to be able to read it in the original.

That's a pretty good wish, Jenny! But what if I want to be able to read Old English and Sanskrit and Latin, not to mention ancient Greek and ancient Mayan? Do those count as currently existing on earth? I am totally on board with this wish.

ReplyDelete