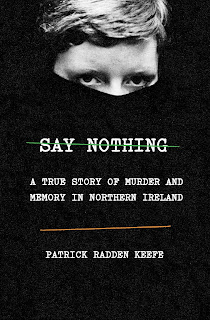

Say Nothing

Say Nothing: A True Story of Murder and Memory in Northern Ireland, by Patrick Radden Keefe

It was complete coincidence that my co-worker lent me this book in March and I felt like I ought to read it right away instead of putting it on the TBR pile where it would sit for a year. But I did read it, and it was pretty gripping, as well as very depressing and now I have a lot of Feelings. I should note that except for this book, my knowledge of Northern Irish politics is gained mainly from osmosis and not any systematic study.

Say Nothing is ostensibly about the disappearance and murder of Jean McConville, a Belfast widow and mother of ten, in 1972, at the height of the Troubles. It's really more about everything the IRA was doing, but the story of Mrs. McConville serves as a focusing lens.

Northern Ireland, in the 1960s, was a fairly poor area, with about 2/3 Protestants and 1/3 Catholics. The Catholics were very definitely an oppressed minority, disallowed from good jobs. The Protestants, as a minority within the entire island, also felt threatened, which encouraged them to continue policies of exclusion towards Catholics. Illegal paramilitary groups and British government forces entangled each other in an ever-increasing spiral of violence.

This book focuses on the IRA -- mostly the Provisionals -- but it's made very clear that the Protestant paramilitaries were doing pretty much exactly the same kind of thing, except they had the British on their side. The Provos considered themselves to be soldiers in a war against an occupying force, and as such they planned to shove the British out of Northern Ireland. The Provo narrative is mainly about two sisters, Dolours and Marian Price, and two men, Gerry Adams and Brendan Hughes. All four were deeply involved in the Provos.

Jean McConville's story is short. She was a Protestant married to a Catholic (not common, but not unknown when they married in the 50s) and lived in Catholic neighborhoods. They had ten children and when her husband died of cancer, she fell into a depression, rarely leaving the apartment where the family lived. One night she was taken by the IRA and interrogated; the next day (or perhaps several days later), she was taken again and just disappeared. No one helped the children, who nearly starved before being taken into various horrible institutions.

Keefe weaves all of this stuff into a complicated but coherent narrative. There are bombings, murders, double-crossings, and a code of silence that makes it all difficult to document. There are, for example, two stories about Mrs. McConville's abduction; that the family had been labeled 'Brit-lovers' after she gave a pillow to an injured British soldier outside her door, or, according to the IRA, she was an informer -- which seems unlikely for several reasons.

Keefe gives quite a bit of history: such as the bombs, which were in theory supposed to damage property and the economy, thus the British (who owned the businesses). Of course, in actual fact they hurt and killed people and the rest of the UK barely noticed. So they figured they'd take the war to London and make people sit up and take notice. The trouble with bombs is, they're not very controllable. As far as I can see, the IRA's dedication to violence mostly backfired on them.

Gerry Adams seems to have been the guy who decided that politics would work better, and he gradually worked his way through politics until he could get the Good Friday agreement going. In his public career, he always denied ever belonging to the IRA, and his political aspirations really embittered his former companions, who were left wondering why they had done such terrible things if their promised reward -- the British out of Northern Ireland -- was going to be denied. Having committed such violence in their youth, they frequently spent the rest of their lives trying to drink away the memories. Adams comes off as calculating and kind of a sociopath -- albeit also possibly the only person who could put together a cease-fire and agreement.

Keefe only mentions the Omagh bombing and the Real IRA in passing, which I found odd when so much time is given to the ins and outs of the rest of the process. My understanding is that Omagh gave a large boost to the controversial Good Friday agreement. Instead Keefe skips right over it to talk about Boston College's oral history project to collect the testimonies of the people involved, only to be opened after their deaths. That's fascinating too, and it didn't go all that well.

Mrs. McConville's remains were finally found buried on a beach on the Cooley peninsula in Louth. Her children were never really given any solace.

I learned a whole lot. I'd like to read about the 'other' side as well. All of it is very dark and a terrible warning of where human beings can go in the name of a cause, or because of there being two opposing sides. I mean, look at the McConville children; everyone knew their mother was gone and they were on their own, and nobody was prepared to help them, because they were tainted by possible contact with the other side. Surrounded by people they knew, they were left entirely alone.

Or the Provisional IRA members, who committed murders in the name of a possible future, and then murdered their own members as well. Who planted huge bombs and then blamed others for it. Who 'disappeared' people for what, in the end, turned out to be maybe no reason at all. Even their self-justifications turned out to be nothing.

It was complete coincidence that my co-worker lent me this book in March and I felt like I ought to read it right away instead of putting it on the TBR pile where it would sit for a year. But I did read it, and it was pretty gripping, as well as very depressing and now I have a lot of Feelings. I should note that except for this book, my knowledge of Northern Irish politics is gained mainly from osmosis and not any systematic study.

Say Nothing is ostensibly about the disappearance and murder of Jean McConville, a Belfast widow and mother of ten, in 1972, at the height of the Troubles. It's really more about everything the IRA was doing, but the story of Mrs. McConville serves as a focusing lens.

Northern Ireland, in the 1960s, was a fairly poor area, with about 2/3 Protestants and 1/3 Catholics. The Catholics were very definitely an oppressed minority, disallowed from good jobs. The Protestants, as a minority within the entire island, also felt threatened, which encouraged them to continue policies of exclusion towards Catholics. Illegal paramilitary groups and British government forces entangled each other in an ever-increasing spiral of violence.

This book focuses on the IRA -- mostly the Provisionals -- but it's made very clear that the Protestant paramilitaries were doing pretty much exactly the same kind of thing, except they had the British on their side. The Provos considered themselves to be soldiers in a war against an occupying force, and as such they planned to shove the British out of Northern Ireland. The Provo narrative is mainly about two sisters, Dolours and Marian Price, and two men, Gerry Adams and Brendan Hughes. All four were deeply involved in the Provos.

Jean McConville's story is short. She was a Protestant married to a Catholic (not common, but not unknown when they married in the 50s) and lived in Catholic neighborhoods. They had ten children and when her husband died of cancer, she fell into a depression, rarely leaving the apartment where the family lived. One night she was taken by the IRA and interrogated; the next day (or perhaps several days later), she was taken again and just disappeared. No one helped the children, who nearly starved before being taken into various horrible institutions.

Keefe weaves all of this stuff into a complicated but coherent narrative. There are bombings, murders, double-crossings, and a code of silence that makes it all difficult to document. There are, for example, two stories about Mrs. McConville's abduction; that the family had been labeled 'Brit-lovers' after she gave a pillow to an injured British soldier outside her door, or, according to the IRA, she was an informer -- which seems unlikely for several reasons.

Keefe gives quite a bit of history: such as the bombs, which were in theory supposed to damage property and the economy, thus the British (who owned the businesses). Of course, in actual fact they hurt and killed people and the rest of the UK barely noticed. So they figured they'd take the war to London and make people sit up and take notice. The trouble with bombs is, they're not very controllable. As far as I can see, the IRA's dedication to violence mostly backfired on them.

Gerry Adams seems to have been the guy who decided that politics would work better, and he gradually worked his way through politics until he could get the Good Friday agreement going. In his public career, he always denied ever belonging to the IRA, and his political aspirations really embittered his former companions, who were left wondering why they had done such terrible things if their promised reward -- the British out of Northern Ireland -- was going to be denied. Having committed such violence in their youth, they frequently spent the rest of their lives trying to drink away the memories. Adams comes off as calculating and kind of a sociopath -- albeit also possibly the only person who could put together a cease-fire and agreement.

Keefe only mentions the Omagh bombing and the Real IRA in passing, which I found odd when so much time is given to the ins and outs of the rest of the process. My understanding is that Omagh gave a large boost to the controversial Good Friday agreement. Instead Keefe skips right over it to talk about Boston College's oral history project to collect the testimonies of the people involved, only to be opened after their deaths. That's fascinating too, and it didn't go all that well.

Mrs. McConville's remains were finally found buried on a beach on the Cooley peninsula in Louth. Her children were never really given any solace.

I learned a whole lot. I'd like to read about the 'other' side as well. All of it is very dark and a terrible warning of where human beings can go in the name of a cause, or because of there being two opposing sides. I mean, look at the McConville children; everyone knew their mother was gone and they were on their own, and nobody was prepared to help them, because they were tainted by possible contact with the other side. Surrounded by people they knew, they were left entirely alone.

Or the Provisional IRA members, who committed murders in the name of a possible future, and then murdered their own members as well. Who planted huge bombs and then blamed others for it. Who 'disappeared' people for what, in the end, turned out to be maybe no reason at all. Even their self-justifications turned out to be nothing.

I worry that the history is not that far gone and may be reawakened, depending on how Brexit handles the border between the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland.

ReplyDeleteYes! It's all very worrying.

ReplyDelete