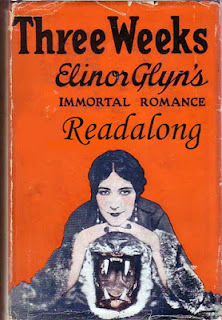

Three Weeks: the Glynalong

Three Weeks, by Elinor Glyn

Three Weeks, by Elinor GlynReading Rambo is a genius at coming up with insane readalongs, and as she said...

I never thought you could actually read Elinor Glyn's books; she seemed like some distant untouchable literary figure, referenced in The Music Man, but whose works were not to be seen by contemporary eyes. Well that is nonsense. They're right there on the internet for free.

This was a revelation to me. I could read Elinor Glyn! So I joined in the Glynalong and here I am, having finished one of Glyn's more scandalous novels, Three Weeks. It's a romance novel of 1907 and it's no wonder it caused a fuss; this story straight-up involves an older married lady seducing a young man and having an affair with him for, you guessed it, three weeks.

Paul is a 23-year-old young man who has fallen in love with the Wrong Girl -- that is, one who is of a slightly lower class and isn't very pretty. Isabella is a tall, strapping young woman with "large red hands" and "large pink lips," so she is worthless. (As an owner of large hands and, ahem, fullish lips, I'm on Isabella's side, and I think she ought to dump Paul's sorry self and go on a trip around the world.) Paul's parents send him to Switzerland in the hope that he'll forget Isabella.

And boy howdy does he! Paul meets The Lady, a mysterious Foreigner (Russian? Balkan?) who sets out deliberately to seduce him -- because she has a rotter of a husband and she wants to produce a baby to secure the succession away from him. It's all put into very high-flown language, though, and Paul is instantly besotted with her. There's a lot about how he worships her -- and a lot of her writhing about on tiger skins, too! Tigers are a big theme.

The Lady forbids Paul from asking her name, or where she's from, or pretty well anything at all. They're just going to live for the moment and their love shall wax as the moon does! So they go off to a mountain where they can stay together, and then they go to Venice, and all in all Paul packs an entire life into his three-week affair.

There are some really awful bits of dialogue. The Lady tells Paul that women will always love their men if they're sufficiently masterful and overbearing. I was particularly annoyed by this bit:

They [ancient Greeks] were perhaps too practical to have indulged in the mental emotions we weave into it now—but they were wise, they did not educate the wives and daughters, they realised that to perform well domestic duties a woman's mind should not be over-trained in learning. Learning and charm and grace of mind were for the others, the hetaerae of whom they asked no tiresome ties. And in all ages it is unfortunately not the simple good women who have ruled the hearts of men. Think of Pericles and Aspasia—Antony and Cleopatra—Justinian and Theodora—Belisarius and Antonina—and later, all the mistresses of the French kings—even, too, your English Nelson and Lady Hamilton! Not one of these was a man's ideal of what a wife and mother ought to be. So no doubt the Greeks were right in that principle, as they were right in all basic principles of art and balance. And now we mix the whole thing up, my Paul—domesticity and learning—nerves and art, and feverish cravings for the impossible new—so we get a conglomeration of false proportions, and a ceaseless unrest."GAH. Blergh. I get that women's roles were overly restricted to the domestic sphere, but I'm unconvinced that the Lady has a solution here. Paul, Lady, you are both terrible.

"Yes," said Paul, and thought of his mother. She was a perfectly domestic and beautiful woman, but somehow he felt sure she had never made his father's heart beat.

OK! So! At the end of the three weeks, at the full moon, the Lady abandons Paul. He promptly falls apart:

...ere his father could arrive on Sunday, Paul was lying 'twixt life and death, madly raving with brain fever.BRAIN FEVER! Amazing. I didn't expect that in a 20th century novel! (I might need a gif here. This is the most gif-appropriate moment I've ever had on my blog.)

And thus ended the three weeks of his episode.

Paul's life is in ruins. After recovering from the nearly-fatal brain fever, he goes home and hates everything, or he travels and hates everything. He's all sophisticated and stuff now, everybody loves him, but he doesn't care a bit:

And all the time Paul spoke he saw no sea of faces below him—only his soul's eyes were looking into those strange chameleon orbs of his lady. He said every word as if she had been there, and at the end it almost seemed she must have heard him, so soft a peace fell on his spirit. Yes, she would have been pleased with her lover, he knew...I like that "strange chameleon orbs" bit -- did I mention that Paul can never decide whether the Lady's eyes are green, or purple, or grey, or what?

Anyway, Paul's father is full of a manly silent sympathy, but he's the only one who Understands Paul. I won't tell you the bizarro ending; the whole thing is pretty weird.

It's particularly odd how all the women characters except the Lady are so denigrated. They are all terrible, according to the author. Paul's mother is too fussy; Paul is condescendingly kind to her and pats her on the head every so often. Isabella is too tall and hearty. Other English girls are insipid and dull. This is not exactly a feminist novel.

It's all incredibly over-written and dramatic and couched in noble language. It must have been absolutely thrilling in 1907, but now it comes off as hilariously overwrought and swoopy, when it's not being outright terrible. Makes for a great readalong, though!

You and Reading Rambo are hilarious.

ReplyDelete