A Winter Riffle of Reviews

I'm hoping to get this year wrapped up in this final week. Which is kind of a lot to leave undone until December 26, so wish me luck!

I've read some neat books and a good bit of fluff in the last couple of months, and I'm just going to run through some of the ones I want to count for challenges...

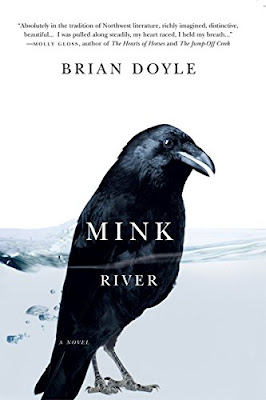

Mink River, by Brian Doyle

Doyle writes the story of a town: Neawanaka, a tiny place on the Oregon coast where a river meets the sea. It's beautifully written, and I highly recommend it.

Read Dangerously, by Azar Nafisi

Written as letters to her

(deceased) father, Nafisi discusses the importance of reading

literature, especially in troubled times. I wanted to save a couple of

quotations:

It is when you cast off the mantle of victimhood that you become a menace, a danger to your oppressor. It it intriguing that in order to cease being a victim, you must accept responsibility for who you are and who you might become -- thus, ironically, acknowledging your enemy and the fact that you might be like him rescues you from victimhood. It is a transfer of power, when you realize the enemy is not the all-powerful, omniscient presence controlling everything we do. We have a choice; therefore we are free. We can choose to become like the enemy -- or not.

Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds, by Charles McKay

This one took me forever, and I had a lot of fun with it. Written in the mid-19th century, MacKay chronicles historic fads, bubbles, obsessions, and movements. The one on alchemy is pretty much a book in itself. We also have haunted houses, the Crusades, popular songs or sayings (the 19th century versions of viral songs), witch-hunting, relics, duels....lots of topics. He's pretty sarcastic about some of them and I marked so many fun sentences that they won't fit here, but I'll try several. Also...I sure would like a set of South Sea Bubble playing cards!

...the most absurd and preposterous of all, and which shewed, more completely than any other, the utter madness of the people, was one started by an unknown adventurer, entitled “A company for carrying on an undertaking of great advantage, but nobody to know what it is.” Were not the fact stated by scores of credible witnesses, it would be impossible to believe that any person could have been duped by such a project.

Their notion appears to have been, that all metals were composed of two substances; the one, metallic earth; and the other, a red inflammable matter, which they called sulphur. The pure union of these substances formed gold; but other metals were mixed with and contaminated by various foreign ingredients. The object of the philosopher’s stone was to dissolve or neutralise all these ingredients, by which iron, lead, copper, and all metals would be transmuted into the original gold. Many learned and clever men wasted their time, their health, and their energies, in this vain pursuit...

The monarchs of Europe were no less persuaded than their subjects of the possibility of discovering the philosopher’s stone. Henry VI. and Edward IV. of England encouraged alchymy. In Germany, the Emperors Maximilian, Rudolph, and Frederic II. devoted much of their attention to it; and every inferior potentate within their dominions imitated their example. It was a common practice in Germany, among the nobles and petty sovereigns, to invite an alchymist to take up his residence among them, that they might confine him in a dungeon till he made gold enough to pay millions for his ransom. Many poor wretches suffered perpetual imprisonment in consequence.

[Paracelsus'] true name was Hohenheim; to which, as he himself informs us, were prefixed the baptismal names of Aureolus Theophrastus Bombastes Paracelsus.

The fashion of the hair and the cut of the beard were state questions in France and England, from the establishment of Christianity until the fifteenth century. We find, too, that in much earlier times, men were not permitted to do as they liked with their own hair. Alexander the Great thought that the beards of the soldiery afforded convenient handles for the enemy to lay hold of, preparatory to cutting off their heads; and, with a view of depriving them of this advantage, he ordered the whole of his army to be closely shaven.

Every age has its peculiar folly; some scheme, project, or phantasy into which it plunges, spurred on either by the love of gain, the necessity of excitement, or the mere force of imitation. Failing in these, it has some madness, to which it is goaded by political or religious causes, or both combined. Every one of these causes influenced the Crusades, and conspired to render them the most extraordinary instance upon record of the extent to which popular enthusiasm can be carried.

A singular instance of the epidemic fear of witchcraft occurred at Lille, in 1639. A pious but not very sane lady, named Antoinette Bourignon, founded a school, or hospice, in that city. One day, on entering the schoolroom, she imagined that she saw a great number of little black angels flying about the heads of the children. In great alarm she told her pupils of what she had seen, warning them to beware of the devil whose imps were hovering about them. The foolish woman continued daily to repeat the same story, and Satan and his power became the only subject of conversation, not only between the girls themselves, but between them and their instructors. One of them at this time ran away from the school. On being brought back and interrogated, she said she had not run away, but had been carried away by the devil; she was a witch, and had been one since the age of seven. Some other little girls in the school went into fits at this announcement, and, on their recovery, confessed that they also were witches. At last the whole of them, to the number of fifty, worked upon each other’s imaginations to such a degree that they also confessed that they were witches—that they attended the Domdaniel, or meeting of the fiends—that they could ride through the air on broom-sticks, feast on infants’ flesh, or creep through a key-hole.

The citizens of Lille were astounded at these disclosures. The clergy hastened to investigate the matter; many of them, to their credit, openly expressed their opinion that the whole affair was an imposture—not so the majority; they strenuously insisted that the confessions of the children were valid, and that it was necessary to make an example by burning them all for witches. The poor parents, alarmed for their offspring, implored the examining Capuchins with tears in their eyes to save their young lives, insisting that they were bewitched, and not bewitching. This opinion also gained ground in the town. Antoinette Bourignon, who had put these absurd notions into the heads of the children, was accused of witchcraft, and examined before the council. The circumstances of the case seemed so unfavourable towards her that she would not stay for a second examination. Disguising herself as she best could, she hastened out of Lille and escaped pursuit. If she had remained four hours longer, she would have been burned by judicial sentence as a witch and a heretic. It is to be hoped that, wherever she went, she learned the danger of tampering with youthful minds, and was never again entrusted with the management of children.

In the twenty-first year of Henry VIII. an act was passed

rendering it [slow poisoning] high treason. Those found guilty of it were to be boiled

to death.

Franklin, the apothecary, confessed that he prepared with Dr. Forman seven different sorts of poisons, viz. aquafortis, arsenic, mercury, powder of diamonds, lunar caustic, great spiders, and cantharides.

[Madame de

Brinvilliers] was convicted of poisoning several persons, and

sentenced to be burned in the Place de Grève, and to have her ashes

scattered to the winds. On the day of her execution, the populace, struck by her

gracefulness and beauty, inveighed against the severity of her

sentence. Their pity soon increased to admiration, and, ere evening,

she was considered a saint. Her ashes were industriously collected;

even the charred wood, which had aided to consume her, was eagerly

purchased by the populace. Her ashes were thought to preserve from

witchcraft.

Comments

Post a Comment

I'd love to know what you think, so please comment!