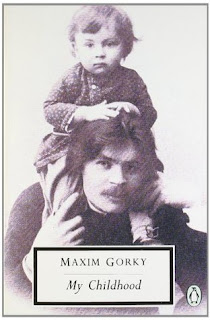

My Childhood

My Childhood, by Maxim Gorky

My Childhood, by Maxim GorkyI've always meant to read Gorky's autobiographical trilogy. I have all three, and I did read My Childhood once years and years ago, but I stopped there and had forgotten all. So one goal of mine this year is to read all three.

Maxim Gorky's real name was Alexei Maximovich Peshkov. He called himself Maxim after his father, and gorky means bitter, which he was. Born in 1868, he had a lifelong concern for the plight of the Russian working class poor. He got into Marxism, but he also founded a socialist publication that attacked Kerensky and Lenin (while living outside Russia; he spent time in the US and Europe). Upon returning to Russia in 1928, he became an enthusiastic Soviet, and died in 1936--rumor had it that he was poisoned by political enemies.

My Childhood starts at age 5, at the death of little Alexei's father. His mother goes home to her parents, but spends less and less time there, until she kind of disappears from the book for a long time. Alexei is raised by his grandparents, in a tense and hostile household; Grandfather is usually stern and violent, and his sons are constantly demanding money. There is fighting all the time, and Alexei is often beaten. His consolation is his loving and saintly grandmother, who tells him stories and takes care of him.

Over the years, the grandparents move around a bit. Odd characters come and go, and Alexei learns a bit more about the world, though he is hopeless at school. His mother returns and remarries, which doesn't turn out too well. Two little brothers are born. And then, his mother dies, and Grandfather turns Alexei out to fend for himself. He's maybe twelve, at most.

When I try to recall those vile abominations of that barbarous life in Russia, at times I find myself asking the question: is it worth while recording them? And with ever stronger conviction I find the answer is yes, because that was the real loathsome truth and to this day it is still valid.It is that truth which must be known down to the very roots, so that by tearing them up it can be completely erased from the memory, from the soul of man, from our whole oppressive and shameful life. And there is still another, more positive reason which compels me to describe these horrible things....Life is always surprising us--not by its rich, seething layer of bestial refuse--but by the bright, healthy and creative human powers of goodness that are for ever forcing their way up through it. It is those powers that awaken our indestructible hope that a brighter, better and more humane life will once again be born.

This, I should read. Maybe next year. I am even more interested in his book about Tolstoy and Chekhov.

ReplyDeleteYeah, I'm going to start with these and then I'd like to read Mother and that one, and see how it goes...

ReplyDelete