February Reading, Part the Second

I've been split between really quite heavy-duty books and incredibly light cotton-candy books. I've read four Three Investigators novels in the last couple of weeks -- ones near the end of the series, so not as good as the earlier titles, but still fun. I could tell the last one was different from the cover, and it turned out to be one of some stories originally written in German -- the Three Investigators were evidently hugely popular in Germany, and somebody wrote some sequels that come off more as fanfiction than anything else, I thought. Anyway, on with the February reads:

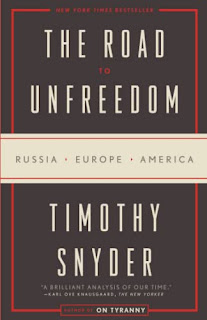

Here are the short versions of some of what I got from this book:

- We haven't been paying anywhere near enough attention, and we're paying a heavy price for that. Russia's policies include weakening Western societies and inflaming polarization, and they have every intention of attacking more of Europe.

- The peaceful and brave Ukrainian Maidan protests of late 2013 - early 2014 were amazing, and a template for us to admire and emulate. (Sadly, I don't think we could do this in our current climate. I've long believed that non-violent protest is the only way to go, but right now, even the most peacefully-planned protest is easily ruined by deliberate violence and looting by groups who are entirely in favor of violence and societal breakdown.) The Ukrainian response to invasion is amazing too.

- We have to get very serious indeed about preserving and strengthening the rule of law and our societal structures. None of this succumbing to apathy or pessimism stuff, and definitely no fantasizing about burning everything down. Do what you can in your sphere, support your community and good governance, donate to what you can, don't just live online and scream on Twitter, vote. We don't have to agree with each other on every single thing in order to take massive steps toward building a stronger, freer society.

...the lesson of 1918 and 1945: that without some larger structure, the nation-state is untenable. [Interesting; never heard anybody say that before.]

...basic Eurasian themes: the precedence of fiction over fact; the conviction that European success was a sign of evil; the belief in a global Jewish conspiracy; and the certainty of Ukraine's Russian fate.

About a third of the discussion of Brexit on Twitter was generated by bots -- and more than 90% of the bots tweeting political material were not located in the United Kingdom. Britons who considered their choices had no idea at the time that they were reading material disseminated by bots, nor that the bots were part of a Russian foreign policy to weaken their country.

For those who took part in the Maidan [the Ukrainian protest against government corruption and violence, 11/13-2/14], their protest was about defending what was still thought to be possible: a decent future for their own country. The violence mattered to them as a marker of the intolerable.

One can record that these people [the protestors of the Maidan] were not fascists or Nazis or members of a gay international conspiracy or Jewish international conspiracy or a gay Nazi Jewish international conspiracy, as Russian propaganda suggested to various target audiences. Once can mark the fictions and contradictions. That is not enough. These utterances were not logical arguments or factual assessments, but a calculated effort to undo logic and factuality.

Neither Russia nor the internet is going away. It would help the cause of democracy if citizens knew more about Russian policy, and if the concepts of "news," "journalism," and "reporting" could be preserved on the internet. In the end, though, freedom depends upon citizens who are able to make a distinction between what is true and what they want to hear. Authoritarianism arrives not because people say that they want it, but because they lose the ability to distinguish between facts and desires.

The Silver Curlew, by Eleanor Farjeon -- Nobody's heard of her now, but I like to collect Eleanor Farjeon, who wrote sort of fairy tales, not always for children. The Silver Curlew is a short novel, a retelling of Tom-Tit-Tot (the British version of Rumpelstiltskin), blended with the nursery rhyme about the Man in the Moon who came down too soon, and a large dollop of Farjeon's own imagination. Poll is the youngest of six children at a mill, and is forever asking questions. Her friend Charlee Loon who lives on the beach lets her take home a silver curlew with a broken wing to nurse back to health, and meanwhile Poll's older sister marries the King of Norfolk because he thinks she can spin twelve skeins of flax in half-an-hour. How everything is brought to rights, and the magical silver curlew healed, makes for an enjoyable nonsense tale.

Sadly I don't have a physical copy. And my e-version doesn't have the Ernest Shepard illustrations.

We start with his voyage to Russia, during which he meets the crown prince, the future Alexander II. (The czar is Nicholas I.) Arriving in St. Petersburg, de Custine mingles with the court, conversing several times with Nicholas I and his wife, Charlotte of Prussia, and even attending the wedding of a minor royal. De Custine likes the czar personally and both feels somewhat sorry for him, caught in the cage of being an absolute monarch (Nicholas' small efforts at liberalism seem to backfire horribly), and also hugely disapproves of the despotism. De Custine realizes that Nicholas is impervious to pity once someone offends him, and is glad to get away from the court. Continuing to Moscow and Nizhny, he describes the country and the people he meets, and it's all quite fascinating. He meditates all the time upon what it means to live in a country where nobody ever speaks their true opinion for fear of punishment. He himself has a government escort with him, who is indispensable for traveling without constant delay and bribery, but who is also there to spy on him.

There's also a nice bit at the beginning where de Custine introduces his family and talks about his parents, who were moderates in the Revolution -- a good way to make enemies on all sides. This is a very enjoyable book; just take it slow.

Comments

Post a Comment

I'd love to know what you think, so please comment!