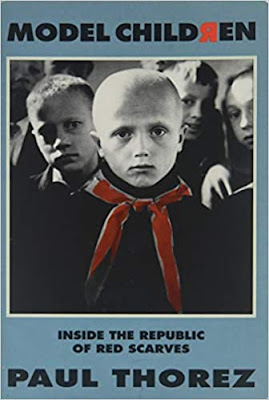

Model Children

This is a reasonably interesting memoir, with the worst cover (from 1990; the original French edition was published in 1982). This is terrible. First of all, it really bugs me when people try to use Cyrillic letters to substitute for Latin ones in order to make a title look Russian. Я is not the same thing as R. Я says ya. It's a vowel. P says R in Cyrillic.

But that is not nearly as bad as this cover photo. This kid is not Paul Thorez as a child, and he's meant to give you a feeling of how desolate and sad Soviet kids must be. The shaven head is meant to evoke prison life, or a place so lice-ridden that every child must go bald. Thorez' memoir is, in fact, a description of life at the very posh summer camp of Artek at Yalta, where children spent most of their time swimming, playing sports, and eating a lot of food. Thorez comments that for years, he thought all Soviet children ate four meals a day.

|

| Worst. Cover. Ever. |

|

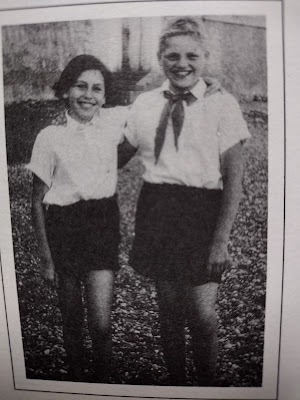

| Actual kids at Artek; Paul is the taller blond one. |

Okay, now that we're past the cover, who was Paul Thorez and why should I read his summer camp memories? (I just picked it up because it promised to be about Soviet childhood, which it really isn't.) Thorez was French, although born in Moscow in 1940. His parents were leaders of the French Communist Party, so there was some back-and-forth between the USSR and France. The family moved back to France at the end of the war and Paul grew up in a Russian-flavored French home in which secrecy was the assumed way of life. His parents were frequently gone for their work, and he and his two brothers lived split lives between their home and their French school.

But for four glorious summers between 11 and 15, Paul got to attend Artek, the summer camp/sanatorium on the Crimean peninsula, which was mostly for the children of Soviet elites. There, kids could swim, play, eat, sing, and have their health carefully looked after. They were one in purpose, and they would be helping to build the wonderful Soviet future.

The last few chapters cover Paul's life as he grows up and his split life gets more and more difficult. He was an idealistic true believer who almost never got to experience actual Soviet life; instead he lived in a luxurious, uncomfortable bubble, while Soviet actions (the crushing of the Prague Spring, for example) fractured his faith. He got into encouraging Soviet avant-garde artists who were definitely too weird for the government. The book fizzles out, because adult Paul is less interesting than child Paul observing Artek.

Artek still exists today. Ukraine ran educational programs there and paid for disadvantaged children's stays. Since the 2014 invasion, Russia has taken it over and refurbished the place again. Russia hosted a few years of summer camps for excelling scholars before Covid hit. I presume it's currently closed.

|

Do you remember Samantha Smith? I thought she was great when I read about her in the Weekly Reader. Here she is at Artek (the one without the scarf). |

Comments

Post a Comment

I'd love to know what you think, so please comment!